Q & A with D.D.Johnston

May 6, 2013

How did the Creative Writing PhD process liberate you / help shape your writing?

Liberation is the right word – it was liberating. First, I was in the unusually lucky position of being funded to study a Creative Writing PhD, so not having to work for a time, being able to focus on reading and writing, was a life-changing privilege. But the liberation went way beyond temporarily escaping wage labour. The Creative Writing PhD affords writers a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to produce a finished output without feeling constrained by publishers’ requirements for economically-viable genre-appropriate manuscripts. And any novelist who thinks she isn’t constrained by those requirements has probably become so used to reading and writing within those limits that she doesn’t see the extent to which they routinely shape her creative decisions. So I decided early on that I had to use this opportunity to experiment with form and content – to be reckless – and this became a kind of mantra. I decided, in fact, that my duty was to write something unpublishable; obviously, in that regard I failed.

How does it feel to be the launch title in a new ‘doctored books’ series?

It’s an enormous honour because I hope and expect that this series will run and run and will, in time, help to define our literary epoch. What I mean is that there remains, in Britain, a grudging resistance to Creative Writing in the academy. Those who oppose the teaching of writing in Higher Education are ankle-deep in the ocean, yelling at the tide to retreat; Creative Writing is here to stay (and on the whole I think that’s a good thing). If we look further across the ocean, we’ll see that the current generation of major American novelists have almost all had some university-level training as writers. And if we’re honest, we’ll admit that American fiction is miles ahead of what we’re currently publishing in the UK.

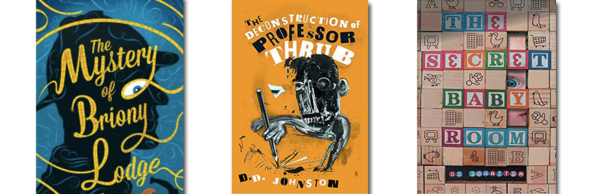

So Barbican Press’s ‘doctored books’ series affords readers the chance to sample the future of British fiction. Over the coming decades, more and more frequently our major writers will go through the Creative Writing PhD process. Some of these writers’ PhD novels will be seen as their juvenilia; for others, the freedom to innovate, the intellectual and (sometimes) financial support, and the emphasis on originality will spur them to produce major work that will shift our whole literary culture. As the author of the launch title of this series, I expect I’m destined to one day be the answer to a tricky literary quiz question: ‘Barbican Press is famous as the publisher of This Famous Novel, That Canonical Text, and This Literary Masterpiece, but who wrote their launch title, The Deconstruction of Professor Thrub? Cue much shrugging and head scratching.

How did your book change, from PhD to novel?

Well, having set out to write something ‘unpublishable’, I never planned or attempted to publish The Deconstruction of Professor Thrub. But Martin Goodman had read the thesis as one of my external examiners, and when he contacted me to say Barbican Press was interested in publishing it, I first thought that he was joking. The thesis was crammed with fake academic articles and tens of thousands of words of historical research, not to mention close readings of 1990s death of the subject novels – and this was all mixed up with the fiction. Frankly, as a lot of academic research tends to be, it was boring.

So the challenge was to publish it in a form where it remained innovative, weird and different, but where it was also an entertaining read. On the one hand, there would have been no thrill to publishing it had it become just another novel in the literary fiction genre; on the other hand, we writers need to be respectful of our readers’ time – if people are prepared to give up their finite leisure time to read our texts, the least we can do is entertain them. So I had to learn that the Ukrainian Civil War isn’t as entertaining to most people as it is to me. Over six months, with a few editorial prompts, I cut back the research and in its place I wrote new scenes, new stories, and even new characters.

I think we’ve struck the right balance. It remains a very unusual book and that it’s being published, with most of its images and photocopied articles in place, owes a lot to Mike Gower, who has done such a great job with the typesetting. The novel’s still written as a PhD that’s been written by an eccentric, love-sick student, who is supervised by an even more eccentric professor. It still asks big questions about the limits of free will, how social change is possible, the pitfalls of Kantian metaphysics, etc.. It still interweaves fact and fiction, plays with ‘fraudulent artifacts’ (to borrow the phrase coined by David Shields and Matthew Vollmer), quotes psychology papers, and satirises our socio-historical moment. It still crashes around the twentieth century, trying to write history in a way that recognises the interminable chain of cause and effect. But it’s also a campus novel that’s full of laughs and scandal and appalling behaviour. It’s a big historical epic that charts the rise and fall of revolutionary optimism. And above all else it’s a series of love stories.

How does the emergence of this list make you feel as a reader?

As a reader, it’s what I’ve long wished for. Most of the young people I know who are really into books don’t read that much British fiction. As I do, they tend to look to America and to work in translation. Why? Well, I think British fiction has been in a rut for a while. On this island there’s a great emphasis placed on elegantly-crafted novels that fit into the literary fiction genre. This is what the British prize system has been focused on for some time (it’s hard to imagine the contemporary equivalent of John Berger’s G, or even James Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late, winning the Booker Prize today). And, whisper it, a lot of elegantly-crafted literary novels are boring. I used to bemoan my students’ aversion to, say, Ian McEwan novels, until, in a moment of honesty, I admitted to myself that I too find a lot of them tedious.

I like ambitious, reckless, exuberant, imperfect books that take you by surprise and mess with you a bit – books like Danielewski’s House of Leaves, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, David Vann’s Legend of a Suicide, Dave Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, David Foster Wallace’s stuff, etc.. Now, there are fun, lively, smart books by British authors, but it’s harder to think of examples – either because they’re not written, or, more likely, because they rarely get the attention they deserve.

Things may be changing a bit – the launch of the Goldsmith’s Prize may help publicise a different type of book; Zadie Smith has tried to do something different in NW (though perhaps it’s still oppressively stamped with the influence of canonical English lit texts) – but I think the emergence of the Creative Writing PhD is a much-needed kick up the bum for British fiction, and over the coming years I’ll follow the ‘doctored books’ list with great excitement. I think it’ll be a thrilling ride. I don’t expect each title to be an elegantly-crafted Booker Prize-winning literary novel (though some may fit into that category); I expect some titles will be a million miles from the sort of thing I normally like to read (and that’s part of the fun); but I look forward to opening each new title, filled with hope and uncertainty. I think this list will put the thrill back into reading.