Barbican First Interview: Karen Stevens

June 4, 2025

As we enter June, we look forward to the release of our final Barbican First title for 2025. To celebrate our new series of debut, short fiction, we’ve been interviewing the writers behind these great books to help you get to know them and their stories a little better, along with their experience of the publishing process so far.

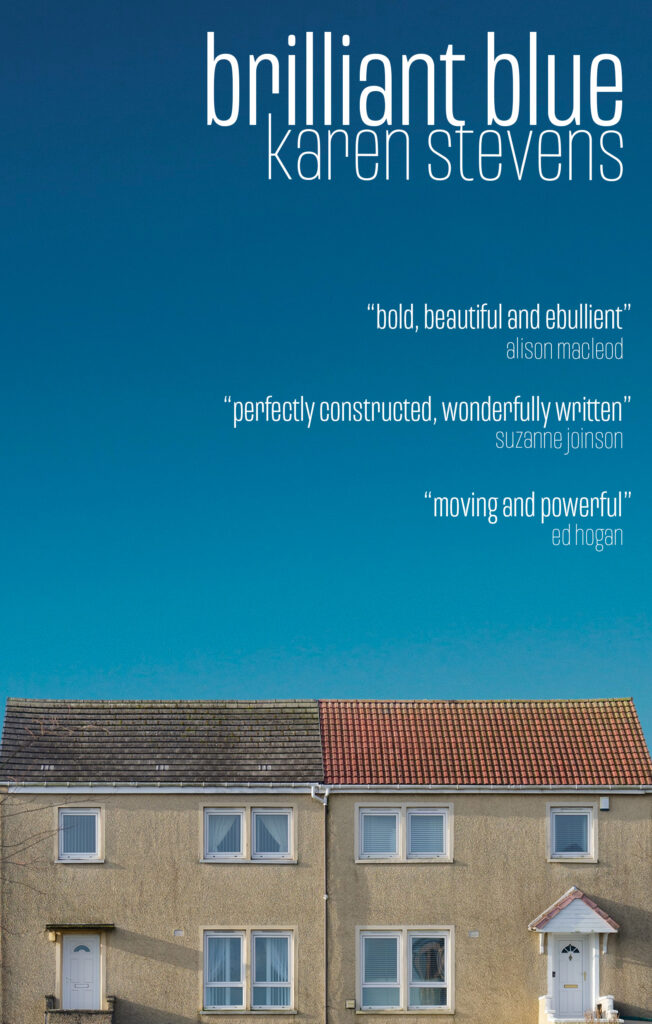

Ahead of this month’s release of Brilliant Blue, a collection of connected short stories set on a South English council estate, we spoke to author Karen Stevens about writing, reading and the working class voice.

Tell us a little about yourself: did you read a lot as a child? Have you always wanted to be a published author? How did you begin as a writer?

Karen Stevens: I grew up in a working-class household and didn’t have access to books because belonging to a library just wasn’t something we did. I was a bit of an oddity in my family because I drew all the time and made little books out of toilet paper to write out my stories (I wouldn’t recommend it – it’s not easy to write on toilet paper with a felt-tip pen!). Though we didn’t have books on shelves at home, I’d power my way through the school reading syllabus and would always buy a book or two with any birthday money I’d get. I’d read the books again and again over the year until the next birthday when I’d buy a few more. I still have those books and they’re very precious to me – especially The Golden Treasury of Poetry by Louis Untermeyer. I was entranced by the different poems and the pictures – especially the ballads. When I was a teenager, I stopped being creative and didn’t bother with school from thereon. Consequently, I don’t have that essential bedrock of reading that fellow writers I know acquired as voraciously-reading teenagers, so I’ve been trying to make up for that ever since – an impossible task. I got back into reading and writing again in my mid-twenties, when I decided I’d had enough of dead-end jobs, and took an Access Course, which helped me get into Higher Education. I studied English Literature, which included some creative writing, and really enjoyed the writing side of the degree. I knew it was important to me and have written ever since (and now teach creative writing), but I never thought I’d have a solo work of fiction published because I felt my stories weren’t mainstream enough for the market, and I also suffered (still do) from imposter syndrome: people like me don’t get published! I just carried on writing because that’s what I wanted to do, hoping that one day I’d find a publisher, like Barbican, who’s keen to hear other voices.

What previous experience do you have with the publishing industry? How did you find out about Barbican Press and the Barbican First series?

KS: I’ve had short stories published in anthologies and magazines, but I’m a perfectionist with writing (a blessing and a curse – maybe more of a curse, actually, than a blessing), and so it took years to get this collection to a standard that I felt confident enough to push out into the world. Barbican bit (thank you), and Martin felt strongly that this collection should be a part of the Barbican First series.

Did you send your manuscript to other publishers? What made Barbican Press stand out?

KS: Yes, I did my homework and sent my manuscript out to other publishers who I felt my work would suit. I got the standard rejections or no response at all, but I’d worked really hard to get the stories to a high standard, and so I tried not to get despondent (I get it – publishers are flooded with submissions – keep going). I was overjoyed that Martin liked my work because I really liked Barbican: the look of the website; how Martin positioned his own taste and ambitions for Barbican, in relation to other publishers. That felt very personal to me. And, of course, the books are so diverse and look fabulous. Lovely covers.

You have some experience of being published, but this is your first full solo book of fiction. How has the process compared so far? Does it match expectations?

KS: The process with Barbican exceeded my expectations. The Barbican team have been totally invested in getting the book into the best possible shape.

What support have you received from Barbican Press regarding the publishing process?

KS: On a practical level, the editing process has been top-notch: attentive and thorough. Martin’s also given good advice and suggestions about getting the book noticed and talked about once it’s out in the world. I’ve never felt dumb about asking the team what I consider to be ‘obvious’ questions.

Do you think the Barbican First series has helped get the best version of your book published?

KS: 100%. From having input into the jacket design, rearranging the order of the stories, to having a chat about whether the word ‘naïve’ should have a diaeresis or not. I love all that final nit-picky stuff!

What inspired you to write Brilliant Blue?

KS: The stories are set around the Duncock Estate, a fictional setting loosely based on a council estate that I know well on the south coast of England. I think the great north-south divide still looms large in our British consciousness. As columnist Owen Jones says: ‘[T]he North conjures up images of being downtrodden and impoverished … The South, on the other hand, is a prosperous land of leafy suburbs’. As I know from experience, however, there’s much deprivation on the south coast, and I wanted to undermine this affluent southern ‘myth’ through my interconnected stories, in which many of the characters are living on the margins amidst financial and social uncertainty.

What authors and books would you compare yours to? Were there any in particular that inspired your book and/or writing style?

KS: I see class as defined by unequal power relationships, and the work of Ken Loach, Livi Michael and Elizabeth Strout are key influences for me in this respect. Their stories of working-class lives lay bare the unfairness that exists in the social gap between poor and wealthy. I’m particularly inspired by how Michael and Strout explore those moments when class lines are crossed or blurred and people become more acutely aware of their position within the hierarchies of class relations. Strout’s My Name is Lucy Barton is an incredibly powerful exploration of this.

Brilliant Blue is a collection of connected short stories that take place on and around a council estate. What do you think readers will find appealing about your stories and characters?

KS: Right now, everyone is becoming increasingly conscious of social inequalities, due to the deepening divide between poor and wealthy over the past decade, or so. As such, I think the stories will appeal to readers because they speak of the here-and-now. Ultimately, though, when we read we want to immerse ourselves in someone else’s world, to step into another person’s shoes, and the stories are very character-driven. Here, we have a bunch of ordinary people leading seemingly ordinary lives, but their inner lives are far from ordinary. For instance, a middle-aged woman takes up extra work in a pub to make ends meet, which re-awakens her masochistic desires. Yes, the social and financial backdrop has driven her to take on extra low-paid work, but the story’s focus is on how this event cracks open her private, inner world. I have to say, I love it when a story makes me laugh, so there’s a good sprinkling of humour running through the collection. I had much fun writing ‘Blissful Blue’ – a story about a revolutionary politics student who returns home to Duncock from university, to work in the local DIY store. At the end of the day, I drew on those elements that I look for in other people’s fiction, and then hoped this would strike a note with readers, too. As Stephen King says ‘You cannot hope to sweep someone else away by the force of your writing until it has been done to you.’

How important was it for you to retain the working-class element of your writing and characters?

KS: I write and think about the world from a working-class perspective because this is where I come from, so it’s not a conscious decision, as such.

How do you think working class characters are usually treated in fiction? How do yours stand out?

KS: I guess the ‘working-class fiction’ label immediately conjures two opposing, somewhat clichéd versions of working-class people: lazy, insular, brutal individuals, or honest, hardworking people who value family and community. For me, Pig by Andrew Cowan is a perfect example of how a working-class story can transcend these stereotypes. It’s a beautifully sensitive and poetic story, in which an adolescent boy’s dreams are pitched against the reality of a town in economic and post-industrial decline. Equally, I want my characters’ stories to go beyond the stereotypical. The people in my stories are who they are and live where they live, and are busy working through their problems and aspirations, just like anyone else. They may be living in more precarious financial situations, but their loves and losses and hopes and trials are as unique and valuable as anyone else’s in society, regardless of class. I’m not sure I’ve answered that question very well – it’s a tough one, actually…

What about working class writers? Why don’t we see more of them?

KS: I guess this is a question for the publishing industry to answer. Why, indeed? The marginalisation of working-class writers is an issue that periodically gains traction, with a flurry of articles (generally by writers who identify as working-class) and initiatives that seek to address the issue, such as New Writing North’s very recent UK-wide literary venture The Bee. Claire Malcolm, the chief executive of New Writing North, said that ‘Talent is classless. Opportunity, however, is class-bound.’ How true. Here’s an interesting figure I gleaned in The Guardian’s article on New Writing North’s venture: in 2019 the number of people in publishing who came from middle-class backgrounds was 60%. Nuff said.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

KS: I included an epigraph from Elizabeth Strout at the start of the collection, in which she says: ‘My hope is always that readers receive a book when they need it; that after reading it they realize – even fleetingly – what it feels like to be another person.’ If this is the take away, then I’d be happy with that.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to get published?

KS:

- Don’t rush. Make sure your work is in the best possible shape before sending it out.

- Do your homework on where is best to send your manuscript.

- Don’t get disheartened by rejection – it’s all part of it. If you love writing – then what else can you do but keep doing the do.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

KS:

Teenager: Steer clear of Pot Noodles.

Early twenties: Ditch the awful perms.

Generally: Be bolder. Stop worrying ‘cause every little thing gonna be alright’ as the great Bob Marley says.

What is your favourite book? (Or what book changed your life?)

KS: Hmmm… that’s so hard to answer because I have so many favourite books for so many different reasons: story, character, style. A book I return to time and again without ever tiring of it is Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë. It’s such a brilliantly immersive story about prejudice, independence and belonging. And it’s atmospheric and strange, too, with poor, distraught Bertha being kept hidden away from everyone.

What are you currently reading? What’s on your TBR?

KS: I’ve just finished reading a friend’s book called Hartisborne by Stephanie Norgate. It’s a novel inspired by the naturalist Gilbert White. I loved the parallels between nature’s straightforward mating and people’s messy loves. I have a huge stack on my TBR list and can’t wait to crack on with it: My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante; Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan; Day by Michael Cunningham; Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang; The Heart in Winter by Kevin Barry. I’ll stop there – I could go on for another two pages.

Do you keep books after finishing or pass them on to others?

KS: I don’t pass on books that have ‘spoken’ to me, in some way. Those books stay at home like obedient children, waiting to be re-read.

How is your bookshelf arranged?

KS: My bookshelves were a mess. I’d spend ages (sometimes days) trying to find a book that I’d want to use for teaching or to re-read. During lockdown, I decided to bring some order to it all by organising them chronologically and into different categories (as you do!), and regretted it instantly (as you do!) because the house was in total chaos for a week. But – oh – the joy afterwards!

Hardback or paperback?

KS: Paperback. Less painful than a hardback when you fall asleep while reading in bed and your book slips from your hands and thuds onto your chest.

Physical, eBook or audiobook?

KS: Physical. I love the feel of a book in my hands. I keep saying I’ll try audiobook, but simply haven’t had the time to get onto it.

Folded page corners: acceptable, or book sin?

KS: Acceptable. I’m terrible with books. I fold corners, crack the spines, write notes, spill my dinner on them.

You’re okay with writing in books?

KS: Yup. I’m generally reading with an eye on what I can use for teaching, and so I underline, make notes to myself, scribble big stars next to paragraphs etc. Oh dear. All capital offences.

What’s next for Karen Stevens? Are you working on another book?

KS: Yes, I have an idea and have written isolated bits and pieces. It’s been brewing for a good while and my plan is to hunker down over the summer. Who knows what will happen when I make a start. Margaret Forster said that when a book is ‘boiling up’ for her, it’s a ‘shadowy vision and odd lines’ – and she’s right.

And finally, if you were not writing books, what would you be doing?

KS: Well, I teach creative writing, and so that’s what I do when I’m not writing (or rather, that’s what prevents me from doing more writing). But in a fantasy world, where finances don’t matter, I’d spend more time with family, take an art class, do some serious travelling.

👉 Follow Karen on X.

Many thanks to Karen for giving us her time and insights. Brilliant Blue will be published on 19th June in paperback and eBook formats and is available to pre-order now from Amazon, Waterstones and other good places where books are sold.

For more Barbican news, interviews and events, be sure to follow us on Substack, Instagram, Threads, Bluesky, Facebook and X, or consider subscribing to our free newsletter.