Writing Short Gay Fiction

February 20, 2025

Lockdown 2020 and the view from my writing table in Lowestoft was of the North Sea. Winds blew. I was going nowhere. Here was my chance to follow Herman Melville out across the ocean.

Ishmael, the narrator of Melville’s Moby-Dick, takes us into the bed he shares with the Pacific islander Queequeg: ‘He pressed his forehead against mine, clasped me round the waist, and said that henceforth we were married.’ There’s no such ardent coupling in Melville’s novella Billy Budd, but a vast amount of male yearning. Before settling down into marriage and writing, Melville spent early years as a sailor. Was he bisexual? ‘Almost certainly,’ says the writer Robert McCrum. ‘As he himself put it: “Deep, deep, and still deep and deeper must we go, if we would find out the heart of a man…”’

Billy Budd is a sailor whose golden youth cheers the hearts of almost all his shipmates. For those of you who don’t yet know this tale of male conflict and desire on a late 18th century man-of-war, I won’t spoil it here. What I will explain is how, when you do read Melville’s Billy Budd, you’ll discover a gap in the narrative that forms the most intriguing missing book chapter in American literature. In the climactic scene from which the tale’s final drama unfolds, Captain Vere, the ship’s captain, is locked into a small stateroom with Billy. The book’s narrator, however, is locked out. The reader is left with speculation about all that happened inside. ‘Billy Budd: Captain Vere’s Account’ tells a complete and complementary, stand-alone story that takes readers into the stateroom for that meeting between the captain and the sailor. I needed to know what happened. Now I do. So can you.

My short fiction is probably the gayest thing about me. Stripped of a novel’s bulk, a story is a more naked and vulnerable form. For me, being gay was a slow blossoming. Gimlet-eyed society was taking note and set to judge (my sexuality was deemed to be criminal when I was growing up) while I was simply busy making friends, loving my dog, growing into shape, discovering the power of words, encountering technology and the natural world and the moral disquiet of adult behaviour. For its characters, novels are something of an endurance task and a question of survival. They face what the world throws at them and strive to come out the other side. The sheer heft of a novel needs its characters to be strong, so as to carry all that narrative weight. In a story they can dare to be themselves. My short fiction explores gay nature with its shields down.

Native American societies have the culture of the ‘berdache’. Over recent decades that French term has gathered colonial shades, and within those societies the term ‘tw0-spirit’ has currency though with a somewhat different meaning. The story as I learned it, in simple form, was that a baby boy was laid down between a bow and arrow on one side and a doll on the other. If he turned toward the doll, then he was judged to be gay: and the family celebrated. They needed no more children because their family was now perfect and complete. Their gay child would be a huge boon to their society.

My own culture knew no such concept of celebration of gayness, only the opposite of shame, so I borrowed it. The theme is played out through ‘The Lovely Life of Arnold’, a sequence of stories that runs throughout the collection. They follow Arnold in seven-year leaps – adopting the concept of the TV series Seven-Up that followed children of my age and time but featured none that were gay.

Most stories have been published in journals and magazines and go back years. ‘Letters to the Parishioners’ drew on overland journeys I took through Greece, Turkey and Cyprus in the footsteps of St Paul. It’s a late twentieth century tale, from when I could maintain some interest in the Anglican church.

You finish a novel, but characters live beyond the novel’s scope. In ‘Queenie and the Boy’ you’ll meet Tom, who has stepped out of the closing pages of my upcoming novel The Boy on the Train. It’s the other of my pandemic tales, pulled into my imagination as I stared out at the North Sea.

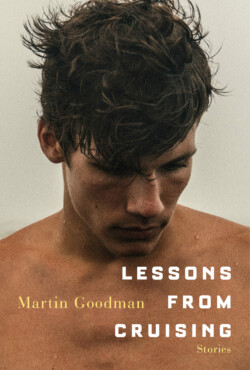

My collection is called Lessons from Cruising – (the title story comes from lessons learned from recognizing youth is something separate to yourself, on a boat trip off Plymouth. Water is another theme that links the stories.) Please enjoy the journey through its pages.

My collection is called Lessons from Cruising – (the title story comes from lessons learned from recognizing youth is something separate to yourself, on a boat trip off Plymouth. Water is another theme that links the stories.) Please enjoy the journey through its pages.